Welcome to New Escapologist, the free and friendly newsletter from the magazine of the same name.

If you enjoy this newsletter and relate to the values it represents, please consider buying our latest magazine in print or digital formats. The new Issue 16 came out this month, subtitled footloose and fancy-free, as we all should be. If you’d like to read more about it before buy a copy, you can do so here.

I’d like to extend a special welcome to this month’s newbies. There’s been a happy uptick in subscribers, partly in response to my article in the latest Idler (my name’s on the cover this time!) and also from my good friend Landis Blair, who must have been talking about me over on his Substack because a good number of his discerning followers have joined us here at New Escapologist. Welcome all!

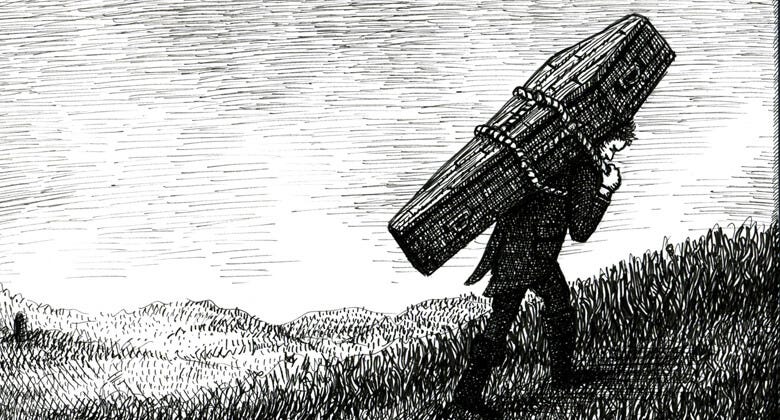

Team Idler might enjoy this archive of my old column I recently put online. Team Landis might enjoy this artwork (below) done by our cross-hatching hero for our magazine some years ago. It was to illustrate a review of the Lyke Wake Walk, a punishing long-distance trek across an old funereal procession route in Yorkshire, England. As it happens, Landis wrote his own account of a long walk — this one between his Chicago art studio and his hometown — in Issue 15.

But enough welcomage. On with the show.

Your friend and neighbour,

Robert Wringham

Editor, New Escapologist

There’s No Law That Says You Must Work

Reader C sends us this quote from the commercial release of the script of Richard Linklater’s Slacker film.

Slacker (1990) was an important antiwork film for much of the ’90s, inspiring the Idler and Douglas Coupland among others.

Here’s the quote from director Richard Linklater:

Work isn’t mandatory in our society. There’s no law that says you must work. You can get by if you can do without. If you’re willing not to have […] a car, nice living conditions, nice clothes, and eat out every night; if you’re willing to go, “I just want to work part-time or not at all and spend most of my time making music, writing, reading, or watching movies,” you can consciously drop out. There’s still enough freedom left where you can manoeuvre.

Let’s pause for a second to remember that the quote comes from 1992. It is more difficult now — not legally but economically and administratively — not to work. But it’s still very possible and what he says is still true.

By “nice living conditions” he presumably means expensive living conditions. I have nice living conditions — clean, easy, happy, centrally urban — on very little money. Friends in cheaply-built but expensive-to-rent housing do not, in my opinion, have “nice living conditions.” They’re in a trap.

The freebies and hand-me-downs in this society are probably the best in the world. For example, I was never really a student at the University of Texas, but that’s a great facility. I’d get my library card for thirty bucks a year and have access to one of the bigger libraries in the South. Just being a citizen, you can take advantage of a lot of things in this culture.

This is still true. A public library card costs zero bucks for tonnes of books. A university library, if they have a special reader pass or similar, still costs a similar amount to in Linklater’s time. The best things in life are very low-cost or even free: walking, reading, being with people, playing music, writing, domestic futzing. All cheap or free.

You don’t need expensive things. They’re junk. And they keep you tied to a job you probably don’t enjoy. As Linklater says, “you can consciously drop out” because, truly, even 20 years later, there’s still no law demanding that you work and “still enough freedom left where you can manoeuvre.”

Elsewhere, in 1995, Linklater said:

I think the cheapest definition [of a slacker] would be someone who’s just lazy, hangin’ out, doing nothing. I’d like to change that to somebody who’s not doing what’s expected of them. Somebody who’s trying to live an interesting life, doing what they want to do, and if that takes time to find, so be it.

101 Uses for a Dead Office

A recent episode of the 99% Invisible podcast looks at the challenge of repurposing useless, ugly, obsolete, recently-deceased office buildings.

There’s a housing crisis in every major city and a surplus of half-empty offices. It’s almost as if our priorities have been completely backwards for decades.

The solution should be to turn these offices into homes. Two problems solved, right?

For various reasons, it isn’t that simple. As much as anything, office blocks aren’t usually in real neighbourhoods. My old office on Concrete Island was a particularly bad example, stranded in a wasteland beyond a tangled nest of motorway. But even better offices are in quite desolate areas. Go for a walk in an office district on the weekend (or on Christmas Day, like I did) and you could hear a pin drop. It isn’t fit for humans [now].

Still, it’s better to reuse a building than to demolish it and start again. That’s what some developers try to do, according to this podcast. I enjoyed hearing about the various problems and solutions. I want them to work.

An interesting nugget is that older, pre-War office buildings convert relatively well into homes… because they have windows.

Did you hear that? Offices used to have windows! And not sarcastic full-wall one-way-mirror windows. Or indeed Microsoft Windows. Just the usual human-scale windows that might make people feel comfortable and at-home.

The post-War buildings present the biggest challenge. The reason? Wait for it.

Air conditioning and fluorescent lights.

Air conditioning and fluorescent lights replaced windows. Oh brave new world.

Ode to a Dressing Gown

As many of my friends know, I spend a lot of time in a dressing gown.

I fancy it’s Sherlock Holmes-ish but I’m probably just being a bum. Then again, so was he.

When people say things about wearing a shirt and tie or Rosie the Riveter-style workwear at home to help them feel fresh or productive, I can’t relate to the sentiment at all.

Each to their own, but being able to wear a dressing gown all day long is one of the main advantages of not having a job.

A dressing gown is practically a friend for life. I’ve always had one but, so far as I can remember, I’ve only ever had three:

1. an Aquafresh-striped one when I was a small boy.

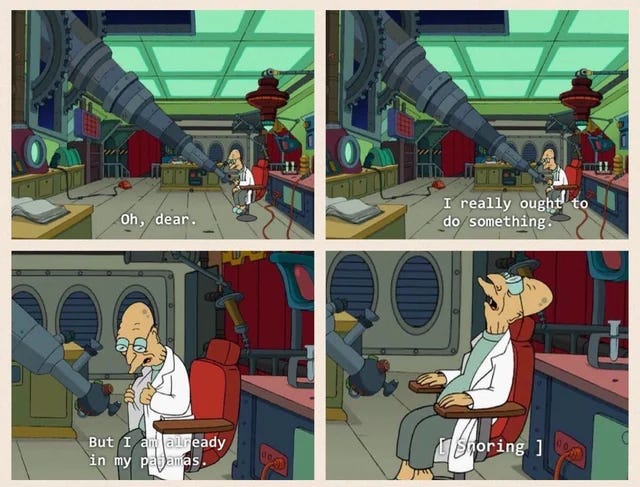

2. an appropriately moody black one as a teenager, which was made of lovely pure cotton. It’s probably my fave of the three, but as I grew longer the dressing gown did not. It soon had a Zapp Brannigan effect and had to be replaced for decency’s sake.

3. the one I have now.

The one I have now has big pockets, which means I can carry stuff around. At present, those pockets contain a handkerchief (as it always does), some anti-itch cream (I’m having an eczema time), a pencil, and an iPhone 6s.

The Workers Stopped Coming In

A quibble about the podcast discussed above (and of other media) is a moment when the host says:

during the pandemic, the workers stopped coming in

That’s true, but the phrasing makes it sound as if the workers just decided not to go to work anymore. As if they stubbornly said, en-masse somehow, “we’re not going there anymore.”

It’s a framing I’ve seen elsewhere in the media too, usually in business-oriented press. “How do we get people to come back to work?” they ask.

Workers didn’t “stop coming in.” They were instructed by the government not to come in. To prevent loss of life.

If workers had the ability to decide — individually or collectively — to “stop coming in” and to work from home where it’s safer and easier and cheaper and better, they would have started doing so in 1997.

Letter to the Editor: Sabbatical

To send a letter to the editor, simply write in. You’ll get a reply and we’ll anonymise any blogged version.

Reader A writes:

Hi Robert,

Thought I’d share that I’ve finally managed to commence a controlled escape from wage slavery in the form of a 12-month sabbatical starting in October, from which I may or may not return. An ideal option for a ‘feartie’ like myself.

Both of your books played no small part in different ways, the first opening my mind up to escaping as a realistic possibility that should be planned for, the second helping to devise tactics to endure my own Concrete Island whilst putting the plan into action. A massive thanks!

Love the new issues. [After reading the books,] there’s some added bonus in receiving the latest copies in the post to then take on the train for the dreary commute!

Feartie nothing. A sabbatical is an excellent and time-honoured escape route.

There must be something in the water, actually. Another reader wrote to tell me about a 6-month sabbatical they’re taking, and a hard-working friend of mine in Leicester is taking a year off too. Long may it continue.

Maybe your sabbatical will contain the seed of a longer-term escape. Maybe, on a quiet night at the movies or under the stars, you’ll have the epiphany you need to extend the break — either for a while or indefinitely.

But it doesn’t have to be a gateway to greater things if you don’t want it to be or if that’s impractical. Let your sabbatical be its own adventure. Twelve months is a phenomenal result.

And that’s all for July, my friends. Please buy an Issue 16 to keep the project alive.

If you happen to live in England, I’m hosting a film screening in Birmingham next month (Aug 24th). It stars Stewart Lee, Jo Brand, Ronni Ancona, Neil Mullarkey, Robin Ince, Simon Munnery, and Meeeeeee. It’s not a New Escapologist production, but it tells the story of the Iceman: a fiercely independent and eccentric one-man art production force (who we interviewed as an example of practical Escaplogy in Issue 14, actually). COME ALONG if you’re able, but buy your ticket asap because it’s going to sell out.

Summer loving,

Robert Wringham

www.newescapologist.co.uk