Hello everyone. The newsletter is late this month because (gasp appropriately, please) I’ve been working on the new print edition. My days are filled once again with the right kind of work.

Yes, Issue 14 (Vol. 2, No. 1) is almost complete. I have 88 pages of original content edited, typeset and practically ready to go. Only the cover art, some test prints, and the inevitable period of fine-tuning remains. The line-up of writers, artists and interviewees is remarkable: truly the dream team of Escapology. By this time next month, you’ll know what’s in it.

I was hoping to have launched the Kickstarter by now, essentially allowing you to buy the new issue, but Kickstarter’s rules forbid me from launching until my novel is shipped next month. Sorry. Hopefully this won’t cause a delay with getting the magazine out in June. I have a plan. And I’ll hold fire in the meantime. Send caffeine!

Your friend and neighbour,

Robert Wringham

www.newescapologist.co.uk

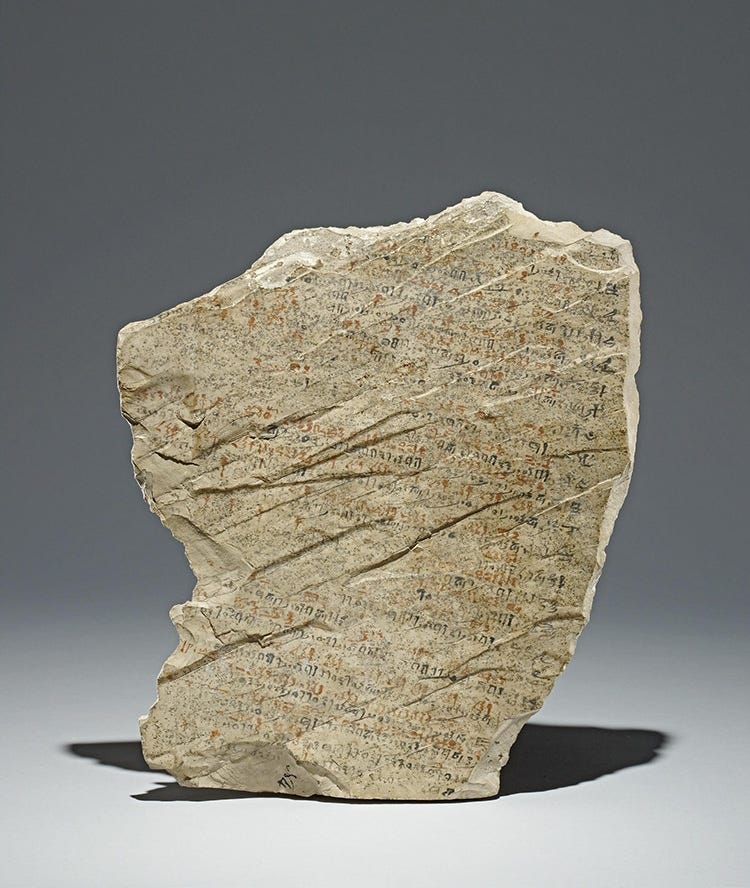

Skive Like an Egyptian

Well, this is delightful.

It’s an ancient Egyptian tablet (called an Ostracon) detailing the reasons cited by workers for getting time off.

Examples include “stung by a scorpion,” “wife menstruating,” “pain in the eye,” and, the best one by far, “brewing beer.”

Try them yourself. They’re time-honoured at least.

Space Man

This quote comes from an episode of This American Life. It’s a work-related story I’ll discuss in more detail presently, but this particularly moment (as devastating as it is) isn’t quite on-theme for the main post. Here goes:

Most of our lives are spent finding parking for the job we don’t want to do. […] And after any number of years, those routines accumulate, and that’s more or less your life.

What the heck? That’s one of the grimmest things I ever heard. A life spent finding parking. Maybe it’s not typical. Not everyone drives. Not everyone lives in New York City, as this correspondent does. But if just one human life is spent this way, it’s a tragedy.

I’ve said before (in The Good Life, perhaps) that the times I’ve felt the most desperately unhappy are the moments when I’ve been preparing to do something I don’t want to do. Walking up the hill to college, for example. I could handle the actual “college” even if I didn’t want to do it. But the walk up the hill was an insult. The quote tracks.

This End Up

Since last month’s discussion of the escape of Box Brown, the idea of packing oneself into a crate and travelling covertly to another land has become almost appealing.

Even I, quite a tall man, enjoy the idea and I don’t even have much to escape at the moment. I just love an adventure and like a good deal. Besides, it can’t be much worse than Ryanair.

I have, of course, been reminded me of the Welsh teenager Brian Robson, who mailed himself home in a crate from Australia in 1965. He described the experience as “quite horrific,” taking four days and frequently being stored upside down. Robson’s box was redirected to the US, where he was found and then grilled by the FBI before being repatriated to London. So it sort-of worked.

And then Wikipedia has a list of others who have achieved (or failed) similar feats:

[Athlete and smuggler] Reg Spiers mailed himself from Heathrow Airport, London, to Perth Airport, Western Australia, in 1964. His 63-hour journey was spent in a box made by fellow British javelin thrower John McSorley. Spiers spent some time outside his container in the cargo hold of the plane and suffered from dehydration [by the time] he was offloaded onto the tarmac of Bombay Airport. He arrived in Perth undetected and returned home to Adelaide.

Charles McKinley (age 25) shipped himself from New York City to Dallas, Texas in a box in 2003. He was attempting to visit his parents and wanted to save on the air fare by charging the shipping fees to his former employer. However, he was discovered during the final leg of his journey having successfully travelled by plane.

Did you catch that part? Charles “saved on the air fare by charging the shipping fees to his former employer.” What a hero.

An inmate (age 42) serving a seven-year drug conviction sentence in Germany escaped from a prison by climbing into a box in the mail room which was picked up by a courier in 2008.

Hooray!

The Acquired Inability to Escape

This is “The Acquired Inability to Escape,” a sculpture by Damien Hirst currently held by the Tate.

The descriptions at the Tate’s website and at Art UK focus on the materials and, especially, the cigarettes. The elements of office furniture don’t get much of a mention.

The work is obviously crap but I like the word “acquired” in the title. It’s the idea that one learns that escape is impossible, overriding a more naïve set of beliefs, which may in fact be more useful. I think this is right: most people learn (from parents, teachers, social cues, television) that escape is not an option. But if you’re lucky enough never to learn that, you’re laughing.

Hirst says, “I like escape formally, as an idea. There’s a religious element to [this work]… A spiritual, not physical escape, if you decide to choose it…”

The Monster in the Pit

I listened to this week’s This American Life from under the bedsheets, wide awake, at about 2am. I listen to podcasts to fall asleep but this one didn’t have the desired effect. I found it riveting.

It was delicious to me because:

1. It’s a classic story of workplace woe taken to an absurd degree;

2. It’s a real example of a “Groundhog Day,” which is something I always enjoy;

3. It reflects badly on Andrew Lloyd Webber, who I hate;

4. It confirms my feelings about Phantom of the Opera, which I dislike;

5. I remember being moved by Gary Wilmot singing “Music of the Night” on TV when I was a kid, so maybe my relationship with Phantom isn’t as simple as merely disliking it.

The story begins with the profile of a trumpet player, Nick Jemo, in New York City circa 1987. He doesn’t get much work. His life is spent sitting by the phone, waiting for gigs. When he’s given a job on the all-new Phantom of the Opera on Broadway, he’s overjoyed. Surely it will pay the bills for a year or more. He celebrates by buying coconut water, which would normally feel profligate.

Phantom ends up running for 35 years: career-length financial security for one trumpet player, and also for the other musicians he sits with each night in the orchestra pit. Unfortunately, it’s a living hell.

It’s dark, cold, and cramped in the pit. Worse, the job is mind-numbingly repetitive. The musicians–creative people with good hands and brains, all of whom trained at the world’s best music schools like Juilliard–have to play the same abysmal score in precisely the same way every single night. They hear the same lines coming from the stage. The same audience reactions. The same chandelier come crashing down at the end of Act I.

He’d never been in a situation like this where everyone seemed so locked into routine. His colleagues would sit down in their chairs at the exact same minute every day. There is a cellist who would say, “Marvellous,” every time Nick asked him how he was doing. There was the first horn player who would pull out a stopwatch every single night to time how long the second horn player held a note in one of the songs. Some days it would be 17 seconds, other days 16.2.

As in many jobs, the colleagues got on each other’s nerves. But in this environment, people became absurdly sensitive:

In the pit, you notice everything. The way your neighbour blows out a spit valve, the way someone brags about their kids, the smell of someone’s perfume. Every little annoyance, every perceived slight, accumulates.

At the end of 30 years sitting just inches away from your co-workers, you lose all sense of proportion. Your enemies turn into monsters. For [oboist] Melanie, the monster in the pit* was always a trumpet player named Francis Bonny. Everything he did drove Melanie nuts, from the black biking shorts he wore in the pit, to always eating his dinner in the locker room with his back turned to her.

(*I was hoping “The Monster in the Pit” would be the name of this segment, but it’s actually “Music of the Night after Night after Night,” which is also excellent).

I can’t help thinking that this is all deliberate torture, that Andrew Lloyd Webber is the ultimate sadistic boss:

Andrew Lloyd Webber wanted the best of the best for Phantom, which means the pit will always sound good, though it also creates some creative and spiritual problems for the players, who have to get through the score night after night after night.

Personally, I find it highly likely that Lloyd Webber’s dream was to lure and trap some beautiful people in a pit.

And they really were trapped. Like many people with rarefied talents, the musicians felt that they couldn’t leave. To leave would have meant sitting at the phone again, waiting for the next gig. And the next lifesaver might just be another Phantom anyway.

It felt unending and precarious. Because of the way successful Broadway shows are extended, season after season, the musicians never really knew when it would end. Or if it would ever end for them, since so many of them were dying of old age, one by one.

Finally, after 35 years, Phantom of the Opera has closed on Broadway. Nick Jemo and his colleagues (apart from the ones who died) are free at last.

Letter to the Editor: As if into Quicksand

To send a letter to the editor, simply write in. You’ll get a reply and we’ll anonymise any blogged version.

Friend McKinley writes:

The “vast grey sleep” reminds me of a line from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s memoir, Wind, Sand and Stars, when he catches a bus to the airfield for his first ever mail run as a pilot (which was very risky and glamorous at the time).

Finally I saw the old-fashioned vehicle come round the corner and heard its tinny rattle. Like those who had gone before me, I squeezed in between a sleepy customs guard and a few glum government clerks. The bus smelled musty, smelled of the dust of government offices into which the life of a man sinks as into a quicksand.

I see now that I had misremembered it. He’s comparing the office dust to quicksand. I had the phrase remembered as “one of those government jobs into which the life of a man sinks as into a quicksand,” which certainly feels like the people I know who got a job in the public service with every intention of getting out in a year or two. He’s saying the exact same thing, just sticking closer to his metaphor.

I now have this sudden fear that I first came across the line in Escape Everything! and it’s what prompted me to read Wind, Sand and Stars in the first place, the timing is about right. Regardless!

*

Wringham Wresponds:

That’s a nice quote and it’s not one from Escape Everything!. The closest thing I remember quoting is this moment from a J. M. Coetzee memoir.

Something I failed to note about that quote is that, as well as being an early example of using a computer to skive, it’s an early example of computer programmers working devotedly for no extra money into the night.

The Escape of Wolf Tivy

People miss that escaping this meaningless servitude to our own capital was Thoreau’s main point in Walden. You don’t actually need the money; in reality, the money needs you to give it a worthy purpose, but everyone gets this backward.

This is a well-told escape story, complete with the philosophy behind it. Thanks to friend Marcus for sending it our way.

(Since originally posting about this at the blog, reader Radhika found that the magazine founded by Wolf after his escape is financed by Peter Thiel. Gross! Thiel is a billionaire venture capitalist and an exacerbator of many of the world’s problems, not least via the very existence of Facebook. Friend Tom’s classic essay, With Friends Like These, tells you most of what you need to know about him. Even so, I won’t discourage you from reading Wolf’s essay but please go into it knowing what world you’re on the edge of when doing so. It’s good that we take our escape stories from all quarters.)

So we’re talking about one Wolf Tivy here. He quit his job with with clear and quite modest goals:

I quit my engineering job in 2014. I was good at it and it was good to me, but it wasn’t the future. I was still working out my plans, so I hit the gym, pursued the most interesting and important ideas I could find, and started looking for a wife.

Quitting your job to find meaning is already unorthodox, an act of good faith and personal strength. But once he’d taken the leap something really interesting happened:

When I wasn’t lifting and courting, I was building a network of intellectuals interested in problems of governance from beyond the established liberal democratic paradigm. I didn’t know why it was interesting. In fact, I thought it was a vice. “This is bad for your career,” said the little wage-slave voice in my head, “you should be focusing on more lucrative projects.”

The little voice was wrong. It was through those intellectual networks that I got my next job and built the social capital which allows me and my friends the freedom to pursue the important problems we have been tasked with.

He set up a magazine, which went on to become successful. Isn’t this an example of what I always say will happen? Give up the prescribed life of drudgery, live a little, and the ideas will start to come. Not just the usual “hey that would be cool” ideas but also how it would function, how it would reach people, a sense of the staying power that would be necessary to run with it.

Almost exactly four years after I quit my last real job, we launched Palladium Magazine as the discourse center and beacon by which we would develop our intellectual project and attract more talented collaborators.

“Beacon” has long been one of my key words. I finally talked about it in The Good Life for Wage Slaves. Instead of looking for “a gap in the market” like a dreary businessman or forcing a product nobody needs onto an unsuspecting public like capitalism (or marketing?) wants, create “beacons” that broadcast a signal on a particular frequency to attract the people you want to talk to and the people you want to know. Even if that frequency is a strange one, it’s big world and you’ll find your people. Or rather, they’ll find you.

A lot of what Tivy writes here is centred around the luxury of free time or, as he points out, what the Romans called otium.

There are investments you can’t make from a structured, nine-to-five, narrowly teleological environment. You have to let your life go fallow sometimes, like a crop rotation giving the land time to bring forth new fertility. […] The world is full of ideas and opportunities to explore, but it takes time outside of structure to even adjust your eyes to the landscape of possibility. You are cramped by your job, unable to make the class of investments that is necessary for a life beyond the existing tracks.

This is classic Escapological wisdom. Take a break, let the mind wonder, figure things out. Work out what you want, how you want to spend your hours, what your priorities are, what would be good for your community and for the world.

It’s hard to think about things like that when you’re stuck at a desk in someone else’s office or drilling holes in the street for a gas company. You need time. You need to be able to watch the clouds form into animal shapes in the sky and then fall apart again. You need to dream.

I won’t quote any more because I’d be running the risk of copy-pasting the whole essay wholesale, which would be pointless. Give it a read.

That’s all for another month. Next time we speak, the Kickstarter should be ready and we’ll be on the brink of a whole new era of New Escapologist. Scary.

—Robert Wringham